Henry O. Flipper: Overcoming Adversity through Perseverance

By TLDG, Friday, February 10, 2017

February 1st marks the beginning of Black History Month. Each February, West Point and the Corps of Cadets honor Henry O. Flipper, the first African-American graduate of West Point, by presenting the Henry O. Flipper Award to a graduating cadet who exemplifies the qualities of “leadership, self-discipline and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties”. Flipper demonstrated true courage and leadership in the face of adversity. February is a time to celebrate the inspirational African-American leaders who have led, and continue to lead our great nation. Flipper was featured in the award-winning book “West Point Leadership: Profiles of Courage” (co-authors Dan Rice and LTC John Vigna) and his story is a source of inspiration to all Americans:

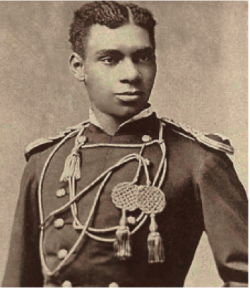

Henry O. Flipper is now a celebrated icon at West Point as the first African-American graduate. But the roller coaster life he lived was far from glamorous; it was fraught with challenges, racism, discrimination, and scandal. But it was also a life of achievement, pride, and success. In hindsight, he was a heroic leader who broke down racial barriers. Yet, he died having been found guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” Although he fought for more than half a century to clear his name while he was alive, he was unsuccessful in doing so. However, ever resilient, even in death he overcame adversity; more than a century later, after being found guilty of his charge, he was posthumously pardoned by President Clinton in 1999 and is now a heroic icon of West Point history.

Henry O. Flipper

USMA 1877

• Born a Slave in Georgia

• First African-American Graduate of West Point

• First African-American Officer in the U.S. Army

• Served with 10th Cavalry in the Indian Wars

• Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior

Photo Credit: National Archives

Born as a slave in Georgia on March 21, 1826, Flipper was schooled in another slave’s home until he started attending missionary school at age 8. After President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, slaves in the North were freed, but in the South, Flipper remained a slave until 1865. In 1869, he was one of the first to attend the newly founded Atlanta University, and the fourth black cadet to enter West Point (on July 1, 1873). The first three did not graduate, and the challenges he faced as the sole black cadet would be daunting. He faced incredible prejudice in an Academy still divided between North and South working toward post–Civil War reconciliation after a war that was in part fought over the slavery issue. Despite West Point’s efforts to integrate blacks into the Academy, the United States was still a society where segregation was the law and blacks did not have full privileges of an American citizen. There was still an atmosphere of prejudice at the Academy, and Flipper was silenced by many of his classmates who refused to speak with a black cadet. Despite the challenging environment, in 1877, he graduated 50th in his class of 76 cadets and was commissioned as an officer – the first black officer in the United States Army.

He fulfilled his personal dream when he was assigned as a Second Lieutenant in Troop A of the 10th Cavalry assigned to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, leading black soldiers in one of two Cavalry Regiments called “Buffalo Soldiers.” In 1879, he was in temporary command of Troop G as Acting Commander. While at Fort Sill, he was responsible for designing and building a ditch to resolve a drainage problem that was causing a malaria outbreak from stagnant water. The engineering project was so successful, the ditch he designed and built bore his name and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977 as “Flipper’s Ditch.”

In May 1880, his unit was assigned to Fort Concho, Texas, in pursuit of the Apache Chief Victorio. In the spring of 1881, Flipper was acting as quartermaster when an event occurred that would change his life. The details of the events still remain unclear even years later. Money was missing from commissary funds, which Flipper discovered and was personally investigating. His new commander had created a challenging and racially charged climate as Lieutenant Flipper was the only black officer in the Army at the time. While investigating the whereabouts of the funds, Flipper lied to his commander in order to buy more time to discover the reason for the loss or the whereabouts of the funds. He was court-martialed for embezzlement and “conduct unbecoming of an officer.” The embezzlement charge was dropped for a lack of evidence, but he was still discharged from the Army for having lied to his commander. He was the first officer in the history of the Army to be charged with conduct unbecoming.

He spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name, although all of his efforts were unsuccessful. He owned his own company for a short time, worked as a translator for the Senate and a special assistant for the Justice Department. He died at age 84, in 1940, never knowing that his name would one day be cleared. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, his records were reviewed, and the Army officially evaluated his case in 1976. The evaluation determined that although Flipper had lied, the dismissal was too severe, and he was given an honorable discharge effective June 30, 1882. In 1999, President Clinton pardoned Flipper, restoring his name to the honorable status well earned by an American hero who blazed a trail in history to help end discrimination and reduce racism after the American Civil War.

Even though West Point and the Army were far ahead of society in integrating African-Americans at that time, it was still a very discriminatory and racially charged environment. It is hard to imagine the struggles, racism, and discrimination that Flipper overcame to graduate from West Point in 1877. Every year, on the date of his birth, March 21st, all cadets celebrate “Henry O. Flipper Day.” His bust is displayed in West Point’s Jefferson Library in the Haig Room, deservedly beside other iconic statues and busts of West Point legends: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Bradley, Pershing, Patton, and Schwarzkopf. He is remembered as an American hero, who helped break down racial barriers.

Rice, Daniel and Vigna, John. "West Point Leadership: Profiles of Courage" 2013. Pages 232-233.